Gender Stories

Gender Stories

Jamie Windust & Alex Iantaffi in conversation

Use Left/Right to seek, Home/End to jump to start or end. Hold shift to jump forward or backward.

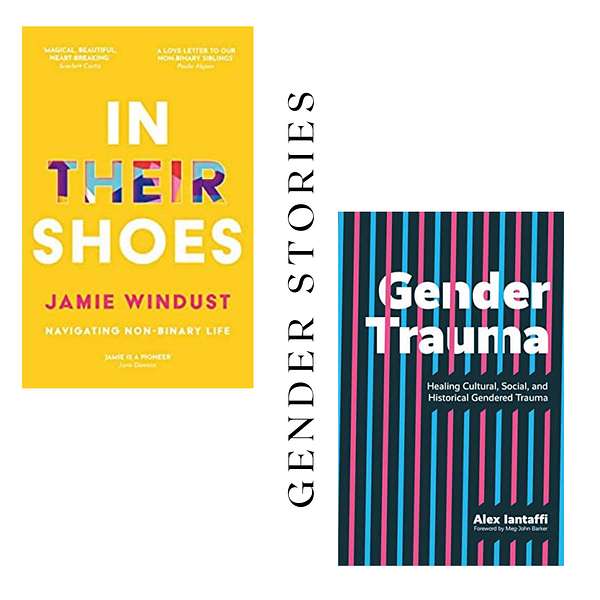

This episode was recorded live on April 21st, 2021 for London's fabulous, independent bookstore Pages of Hackney. Jamie Windust, model, presenter, contributing editor at Gay Times, TedxLondon speaker, and author of In Their Shoes discusses their book and writing process with Alex Iantaffi, author of Gender Trauma. You can follow Jamie on Instagram and Twitter. You can order In Their Shoes and Gender Trauma from Pages of Hackney, your nearest independent bookstore, or wherever you get your books.

Instagram: GenderStories

Hosted by Alex Iantaffi

Music by Maxwell von Raven

Gender Stories logo by Lior Effinger-Weintraub

Everyone has a relationship with gender. What's your story? Hello, and welcome to Gender stories with your host, Dr. Alex Iantaffi.

Alex Iantaffi:Hello, and welcome to another episode of gender stories. Aear listeners, this is your host Dr. Alex Iantaffi. This episode was recorded as an Instagram live for Pages of Hackney and Pages of Hackney is a small award winning bookshop on the lower Clapton road in London United Kingdom. Their priority is to be a friendly, welcoming community bookshop that feels accessible and inclusive. They want each customer to feel that the bookshop is for them. And they do their best to give their customers individually as much time as far as the can. It's also important to them to support the issues and authors that they believe in. And to give a platform to marginalized voices in publishing. They hosted the fabulous author, presenter and model Jamie Windust for a conversation. Jamie is the author of In Their Shoes. They're also contributing editor at gay times, and a speaker for TEDx London. This was the first time that Jamie and I met and we had a lot of fun talking about our books. And what's it like to be a non binary author, and I hope that you enjoy this conversation as much as we enjoyed having it. Thank you for listening.

Jamie Windust:Hello, my love. How are you?

Alex Iantaffi:Honestly a little bit nervous about this whole Instagram live thing? But now we're both here. I can relax, how are you?

Jamie Windust:Don't be stressed. I'm good. I'm good. How are you? You look brilliant.

Alex Iantaffi:Thank you. Likewise, I love how we can do this across time and distance. Thank you to the to the Internet technology.

Jamie Windust:This was the technology we have nowadays.

Alex Iantaffi:I know. This is fantastic. I'm so excited that we get to share the space together. Oh, I'm gonna follow Joe's beautiful Instruction. And I'm going to let everybody know that both Jamie's brilliant book In Their Shoes, and my book Gender Trauma are both available to buy from Pages of Hackney. We're still trading online, as well as being open from browsing. And you can order from their website, I believe the link is in the bio. And you can collect the book it can be delivered by bike to you if you live in Hackney or it can be posted probably anywhere in the world. And this event is free for you to attend. However, you can still show your support with a donation and all contributions for this event will be donated to sister space, a community based nonprofit initiative created to bridge the gap in domestic abuse services for African heritage women and girls. So thank you for your donation if you donate and welcome to our life. Anything I've forgotten?

Jamie Windust:No, no, no, no till I mean, I'm just still very impressive that Delivering books by bike I think that's great.

Alex Iantaffi:That's what I thought too. When I saw that. I was like, that is very impressive. Right? What should we do like this is very transparent moment of transparent process. We both have a book, we can talk about it, we can read from it. What would you like to do today?

Jamie Windust:Absolutely. Well, I'm very interested in your book. So let's start there. Start gender trauma, what made you so we do like a back and forth. Okay, so we can ask each other? What made you want to dive into an intense topic? But also a very cathartic one. What made you want to explore that?

Alex Iantaffi:And a beautiful question. Yes. Well, I feel like I've always been intrigued by this idea of gender since I was like a little kid, right? Even before I read gender theory, and the battler and all that good stuff. I remember being like, you know, six or seven and wearing sweatpants and having short hair and people who think I was a boy. And I didn't know the term gender euphoria, then but I knew there was something very suspect about gender. If a pair of pants and a haircut could make people think I was a completely different gender, which I found quite exhilarating. And you know, and even as a teenager, I would joke that dressing suddenly felt like drag and people be like, it's not drag. That's who you are. And I was like, but you know, and this was like the 70s and the early 80s. So it's not like we were surrounded by trans or non binary model models at the time. But as well as this moments of gender euphoria and playing with gender, I was also really aware of how impactful kind of the rigid gender binary was in my life. And in the lives of those around me, you know, kind of, for example, in divorce wasn't even legal. When I was born in Italy became legal that year. Abortion was illegal, I remember when my country voted for abortion. And so just realizing kind of how much is tied up with this idea of gender, and then kind of getting older and getting into the scholarly work. And one of the ideas that had or in the last few years was, you know, we all seem to carry some trauma when it comes to gender in different ways. You know, really, I do think that transgender non binary folks really bear the brand, and especially folks of color. And also all of us are really impacted by this weird, rigid gender binary, which is it fairly modern idea, and it's also very settler colonial idea. So, you know, as I was training people and brewing this idea, I got talking about it with my John, you know, my co author and friend and a writing partner of many years now. And they were like, you've got to write this book. And I was like, Yeah, but is it gonna make sense to anybody else, but was not in my brain, and was making all these connections. Turns out, if that makes sense to people, but I have to say it was the hardest book I've ever written. As I was writing it, I was just feeling the heaviness of it, you know, noticing the freeze responses in my body, really needing to take a lot of breaks from writing it. Noticing even nightmares at night, sometimes when I was writing it, because I was really delving into like, a really heavy side of not just my own experience, but the collective trauma that I think we all carry about gender. But the more I talked about it with other people, and the more things connected with them, the more I knew I had to write it, I had to, I hadn't seen anything out there that made this connection. So in some ways, my book doesn't really, it's not new research, it doesn't say anything revolutionary. What it does is weaves together things from different disciplines. It weaves together different ideas in one framework that I haven't really seen many people use, especially in academia, or to train therapists or educators. And so I really felt that given that this book had been in my brain for like, five plus years, I had to get it out there. And I had to see whether it would make sense to other folks. I don't know, does that answer your beautiful question?

Jamie Windust:Yeah, no, definitely. I love that I think it's really important that you and I relate to this massively. They know as queer and trans people, when it comes to telling stories or writing about our lives, it can get very difficult and I think what is great is that you in the publishing world. We we can find very supportive allies that can help us to understand that. You know, sometimes we need to not write for a month, or sometimes we need to put this down because you know, where we're essentially like, like you've just described judging our lives and putting it out there and hoping that other people can make sense of it, or relate to it. I think it's really great that you've done that.

Alex Iantaffi:I was gonna ask you a very similar question in terms of your own process, because it's so vulnerable, right? And in some ways, you know, at least when it comes to gender trauma in my book, I can hide a little bit behind scholarship and academia, even though there are personal stories in the book too, because that's how I write I can even when I write academically, I can't take myself completely out of the writing. But you know, your book, there's so much vulnerability, so much openness. And I very much echo that it's really good to have added or to understand when we need to take breaks. But I'm really curious about what motivated you to write your book and why your process was like in writing that book.

Jamie Windust:Yeah, I think my main motivation was that there was so much in my work as a writer that I felt like I was only scratching the surface of so the context like a couple, kind of around six, seven months before I'd gone full time freelance as a writer, and I was writing quite a lot of what I would now describe as quite like top line uses around queerness and transness. So very much kind of quite palatable pieces as it were. So you know, things that are quite introductory things that are quite education focused and kind of like, how tos and that kind of thing, which you know, are valuable resources. But what I found was that I was only really scratching this office with those things. And I've always written, the majority of my writing is not intended to be published. It's just, it's just the easiest way for me to communicate my thoughts, my practices, my interactions, you know, all of those things. And I think that my process in my statement was very similar to what you described. I was sharing parts of myself that I've never shared before, like family and like, discussions around. Kind of my childhood, those, those were areas that I'd never really investigated before, and then produced something coherent. So it was it was difficult. Again, like you I took a lot of breaks, I had a lot of meaningful conversations with my publishers and my editors, I started therapy alongside the book, that not as a tool to make the book better, but as a tool for me to take what I've realized, and in writing and to take it there and then evolve the thought process and evolve the trauma and kind of put a full stop on it, I guess. So yeah, it was a, I wrote it in a year, which was really nice. I was worried that I was going to have quite a short amount of time. But yeah, when I looked at now, I see it as almost like a timestamp. I'm like, right, this is what I was thinking, at this point in my life. You know, I wrote it two years ago, this is how I felt then. And it, you know, I don't feel I think a lot of the time, we can feel quite shameful about how we thought previously. And obviously, I'm not enough spouting like right wing nonsense, but, you know, I can see that my thoughts and my process have evolved quite a lot. Which is really, you know, nice to reflect on.

Alex Iantaffi:But yeah, I don't know about you, I love what you said about kind of doing therapy alongside writing. I mean, as well as being a therapist, I have a therapist, because I believe that therapists need therapists. And yeah, when I was writing this book, the stuff that was coming up for me in therapy was really interesting. And, and I really relate to what you said about I've always written as well, even as a kid, there's all this notebooks and pieces of paper where I would write poems, and the poems are like 40 years ago, and they're very different than what I would write now. And but there is almost, I don't know about you, but for me, it was almost as drive to express parts of myself, that maybe it wasn't quite safe yet to express to the world, I realized that writing was really a refuge as well as a flight from everyday reality. And I wonder if that was similar for you? Because I'm just so intrigued by the fact that so many last trans and non binary folks, right? And I'm like, what is it about writing that it gives a, I don't know, I was like, for me, gave me safety gave me a refuge. It gave me an outlet. And I wonder if it was like that for you, as well.

Jamie Windust:Yeah, masterfully. I think that's why a lot of us are in creative industries and creative roles, whether that's writing or you know, fashion, art, photography, all of those things, they are their storytelling. And I think for me, what I love about writing the most is storytelling. You know, not just my story, but being able to produce and share other people's stories as well I find really useful. I think for me, yeah. When I write and I've noticed this at certain periods of time as a writer, more profoundly kind of, during the time when I was writing the book is that I almost have quite a lot of penny drop moments when writing about my own almost like psychic and it just allows me to just say things that I never even thought I was gonna say, you know, when you when what i've what I love about writing that when I get in a flow and when I kind of discover things as I'm writing things come out that I had no idea we're going to hear. Yeah. That is you know, self evolution. I'm like, God I'm I'm evolving without even realizing it. Like my thought is, you know, I'm figuring things out by doing something that I love, and I think that's what I enjoy is being able to be closer to myself. And hopefully when I do you know, with my work with gay time, just when I help other people just do that, is that they can also have that realization because yeah, I agree. It's it's cathartic? Do you find? Just a question for you? Do you find that I think between me and new, there's quite a different than I guess the similarity that combines us is that we are aiming to provide support for other people and kind of warmth through our writing. But I love I love talking to people that take in quite like an academic book. And and in my experience in my writing, I take it in quite like a anecdotal route. Do you find because you say you've got like a mixture of the two in gender trauma? Did you find that quite easy and kind of nourishing to flip between the kind of more academic stuff and how you experience what that academia actually is?

Alex Iantaffi:That's a great question. Um, yeah, it's you know, I think one of my trouble with being a recovering academic, independent scholar, now that's kind of left academia, trying to leave it more and more, as the years go by, is that I can never really fully separate academic knowledge, the radical knowledge from lived experience, right. And as a social scientist, that's not necessarily a bad thing, because I knew that that lived experience was part of knowledge production, and whose story gets told, even in academia, through questionnaires, and research and all this kind of different ways that we have to construct science, right, because science is a construct too that there were certain parts of human experiences that were being left out. And so I always knew that lived experience was really important to bring into academia. But I think for like a good 20 years, I was trying to do that by fore grounding academia first, right. And then kind of just looking at things like I'll do it longer. Here are other ways of doing academic work that really lifted up the voices, from minoritized folks, mostly kind of minoritized folks when it comes to gender and sexuality and relational structures as well. But what I realized when I left academia is that there is a freedom in actually writing in whichever way I want to. And Mac John has been such a good friend and mentor for me in that, because they always encouraged me to be like your voices is great. And you need to write for the general public and providers and write in a different way. And since I left academia, full time in 2015, it's the most productive I've ever been, which was really fascinating. For me, I've written so much more, since leaving the rigid structure because those rigid dogmatic structures just don'twork for me. And so being able to write something like gender trauma, where I can use all this knowledge that gathered over the years, and I can access kind of scholarship and read it, but I can then.. It's almost a process, but alchemy, I can then take all of this, mix it up also through the lenses of my own clinical experience as a therapist and my own personal experiences as kind of a trans non binary queer person with as of like 50 years of life in the world. And I mean, that and writing is that alchemic process for me? If that, if that makes sense, right? There's a pull all of that in the cauldron. And somehow here at emerge, this book that seems to have a lot of different elements, and also the relationship right, the relationship I have with the scholars who have come before me, the relationship I have with the community organizing I've always been involved in and so knowing that knowledge is not just academic, there's so much knowledge in community organizing. That so much knowledge that is ignored, or is then appropriated and commodified. You know, there's like, so much knowledge in queer communities, right, that's been commodified for an academic gaze. And that's really, I'm hoping that's not what I'm doing. That's not what I'm trying to do. I'm actually trying to do the opposite and really honor like that knowledge from community and really tried to demonstrate with my writing with my nonfiction writing, that we can do something different that it doesn't have to be an either or. Right? That we don't have to put academic knowledge here and then leave the experience somewhere else and then just forget about what's happening in community because it's completely separate. Am I making sense?

Jamie Windust:No, absolutely. It's almost ironic that there's a kind of quite a binary with academia and lived experience like and I love what you said about alchemy, you know. You mix them up, and then your writing process is that is that kind of experiment of you know, what's gonna come out. And I think that's really helpful because I remember when I was when I realized I was trans and non binary, I felt quite, almost pressurized to know all of the theory to, you know, to fully know about absolutely everything about the history and everything. And, you know, obviously that's important, and it's a gradual learning process. But I think there's an argument that you don't have to know your queer theory in and out to be able to appreciate the rich history of our community. I think there is an argument that you do need to educate yourself on lots of history. That's absolutely, that's not I'm not saying don't do that. But I think. Yeah. In wider society, how academia is revered as something that is very proper, and you must do that, I feel like we are amongst the queer community, there is also an affinity with that idea to that. How dare you not know, this very niche theorist? And it's like, Well, I'm afraid I don't. So I sort of say of... Yeah, if anyone has any questions do, do pop them in. But yeah, in terms of like writing, for me, I'm thinking about a future work at the moment. And there's a lot of stuff that's come up recently that I have had discussions with publishers and editors about the idea of like, what queer people should write, you know. When we are given platforms, or when we have ideas, or when we approach publishers, you know, even though we may have experience as a writer and be have a broad portfolio, there is still an expectation on us to write about queerness and transness. Do you find that there's, do you find it difficult to approach writing in a way that isn't specifically focused on gender? If you didn't want to? Or do you? You know, you might have been, you might be happy to do that. Continually. That's absolutely fine. But do you? Do you feel pigeonholed slightly at times?

Alex Iantaffi:Oh, absolutely. I love that. You're bringing it up on this? I have so many thoughts right now, from what you're saying, Jeremy? You know, first, I love what you said about that pressuring queer communities, especially white queer community to be quite academic and heady about our own identities and histories. And I was like, what there's so many other ways of like, connecting to queer history that is now just through kind of academic books. And, yeah, I've felt that pressure kind of goes hand in hand with your other question of whether I feel happy to write about, you know, whether I feel pigeon holed. I think it's a yes. And for me, you know, one way I was always fascinated by gender, my PhD is in what used to be called women's studies. There wasn't even Gender Studies at the time. So that ages me a little, you know, I was brought up a second wave feminist, which is also really interesting to see, all this folks say, Well, you know, it's an old people thing. I was like, I'm 50. And I was brought up a second wave feminist. And also, like, older trans people exist. I know, trans and non binary folks were like, 60, and 70. And 80. You know, it's like, this is not a young people's game, even the non binary identities, you know, we might use different words, but there is a history there that I think gets lost sometimes in this focus on academia. And so in one way, like, I've always been fascinated by gender, and so I've always written about gender in a range of ways. On the other hand, there's almost this expectation that I will write about gender. With that, that's all I know about. And not just in writing, but even in my professional career. So sure, I do see trans clients and youth and that's part of my work. But I've been hired to be a consultant for a different program here in town. And there was this surprise that this breadth of knowledge and experience beyond trans people. I was like, I also know a lot about disability and sexuality and neuro divergence and few a bunch of other things that people tend to forget, because what they see is like that trans first, right, and so it's like, you're, you're gonna write about gender. And when you read about gender, it's gonna be about trans stuff, right? And actually, a lot of the things I write even gender trauma. Sure, it is informed by my identity and knowledge, but it's actually about gem everybody's gender. From an intersectional perspective. It does talk about cis people, as well as trans people. It talks about different intersections, same without to understand your gender. It's really actually I think, even though trans and non binary folks have found it helpful. It's mostly for cis folks, and it's really about them examining their ideas of gender. And so I do feel this pressure. And then if you don't fit in, like, if you're not a trans thought or writing about trans stuff, people don't know where to put you, right? It's like, where do you put this book? Is it in LGBT studies, is it somewhere else? And like, where do you put this person? Where's your little box? And I'm like, Well, I don't fit very well in boxes. I'm very blaming all in every way. And, and maybe I don't want to always write about gender, you know, and, you know, thinking about future projects. I mean, I am, a big project is actually writing about sex and disability, because there's so little, and you know, and that's one of my areas as well. And another project is I really want to write about my own experiences as a provider, and how have I become the kind of provider I am, you know, in the mental health field. And that's got very little to do with, with my gender identity, if that makes sense. And yeah, and I'm curious about the same question for you. Are you finding that you feel pressured to like fit in this box? Or?

Jamie Windust:Yeah, no, thank you for your answer. It's really, really useful. And I think there's an element to it. Well, I yeah, I do feel, I do feel pressurized. And I do feel I wouldn't say restricted, but there is definitely an element to it. Where, for example, with coming up with new ideas for another project to buy on, my brain does automatically go sometimes just to the gender lens. But part of me is like, well, of course it does, because that's how I see the world. So I guess in my experience with looking at writing and broader projects, like fashion has always been an industry that I've worked in, I have a degree in and I, you know, that's my area. And I think there's, again, like I say, there's a lens to to it, where yes, I can talk about fashion and gender, in my experience, that is a huge part of my journey. And as you said earlier, it's something that can kind of kickstart a conversation about. But sometimes I just want to, I don't need to, and I think that's what I try and see more of, for queer people, and trans people out there is that, you know. When we get these opportunities, or when we, you know, we work and we receive success or whatever, that we shouldn't feel like we have to be eternally grateful. You know, I mean, obviously, we can be grateful, but there's a level. So sometimes it's, I've noticed this a lot, especially in like, traditionally non queer industry, where they expect you to be incredibly grateful, because they're essentially saying, you wouldn't get this, you wouldn't have this opportunity, because no one else wants you. Or, you know, if I do work that's slightly more mainstream, that is a very a feeling that is in abundance, because they're like, you're used to your kind of queer niche media over here, we're bringing you this way, you should be very grateful. And of course, you know, of course I am. But that needs to be normalized, we need to normalize that because otherwise, we're going to be expected to have to bring up things that we don't necessarily always want to talk about. Because it impacts our mental health, it impacts our lives. You know, we don't I think it's easy to forget, we write about these things, but we also live them. So there has to be some form of cutting off point. Because otherwise, your whole work life, personal life, is just full of it.

Alex Iantaffi:I relate to that so much. And I love what you said about like the expectations of almost being grateful or having to be grateful in a different way that or thinks this folks need to be in certain. And I find it both in kind of the publishing industry. And sometimes even in my own work, like as a provider and an educator, almost this kind of how, you know, almost this feeling of, 'Wow, isn't that enough already that we're considering you at all'. And it's almost like there is a piece of humanity that gets taken away from us in some ways. If I don't know if I'm explaining myself clearly because at the moment, it's more of a feeling in my body when you said that was like, I know that experience. I know what that feels like, you know. And, yeah, the impact on our mental health. I think it's considerable in those moments actually. And and it is sometimes, I think a price that we pay with some visibility. And I mean, my level of visibility is tight. Yeah, I feel, you know, but you know, compared to yours, but even with any visibility, I think there is kind of, yeah, this weight that comes from mainstream media, mainstream audiences. Am I making sense?

Jamie Windust:Yeah, no, definitely. I think visibility is an interesting conversation as well, a lot of people at the moment are talking about visibility. And I think I've always thought that in the industries that I work in, visibility is often seen as kind of the the golden ticket or like something that will, is more, you know, end transphobia or something that kind of papers over all of the cracks. And I think, what I like to see visibility as it's kind of one part of a cog, of a nervous. Because you can't, you can't place people invisible positions or have visibility for trans folks, if you don't have an inclusive environment for them to begin with, or if you don't have accessibility, or if you don't just even have just like a baseline knowledge of what it's like to be trans because not only does that make your representation and visibility tokenistic, it makes it the actual trans people involved and make the kind of pointless in a way, because they don't actually feel included. But outwardly, it may appear that there is visibility, like and in my experience, I've noticed a lot of that in kind of that my kind of modeling world and fashion world, like there's a lot of that that goes on, especially at Pride. Where you just notice that they don't actually really care, because now it's gonna do well. That's why I've kind of moved a bit of my work into kind of more consultation, when it comes to these types of projects. Because, you know, I'm sick of it. I know lots of people in my industry who find it very frustrating. And I was like, well, let's try and do some work behind the scenes first, so that when they do, you know, quite rightly want to make trans people visible, which is not a bad thing, that they do it right. And they do it with the best intention. How do you find visibility as a concept? Do you find it quite frustrating?

Alex Iantaffi:I relate to what you said even though it's a different context that I work in. I do find that sometimes it's like, exploited, sometimes when it comes from the kind of mainstream world, right? It's like, am I just here to take a box? Or do you genuinely see me and see my expertise and my skills, and my value? Right, and also visibility, you know, a lot of us have trauma, because a lot of us have been targeted for not conforming to certain expectations of gender, often. I think that I don't know, for you, or other people. But for me, disability also brings some trauma responses and some fear. Every time I have a book coming out, you know, everybody said, Oh, its so exciting you have book coming out. And I'm like nauseous. My muscles are really tight. And kind of bracing also for like, potentially, kind of hateful responses, I might open my mail, which I did the other day, and found some hate mail from somebody who sent it from our website. You know, and at times, I also find beautiful messages of what my writing is meant to people, and what my visibility means to people. But disability also makes us targets as long as there isn't enough safety, in dominant culture to kind of really protect us to a point, right, there's like, there's no much even just casual transphobia you know, not even just the the point in hate, but just the casual transphobia that's everywhere, can be really uncomfortable in a lot of, you know, and feel really unsafe. And I think it also triggers kind of past trauma for me, for sure. And so it's always that visibility management that people talk about, right? Where am I visible? And how am I visible and how do I kind of also protect myself and, and even within queer community that visibility can be odd because it can set you apart a little bit from other folks who are not as visible and make you even a target within your own community, sometimes in a weird way, and and then it's just, oh, no, it feels challenging. Sometimes I'm like, I need to be really careful about anything I say in public because, you know, it has weight. It's also about taking responsibility for my influence. I'm like, Yeah. I want to be accountable for my power and influence. And also we all carry so much trauma. I don't know, am I making sense? I don't know, if you resonate with any of that, or?

Jamie Windust:No, massively, I think there's.. what you said there about the safety aspect is incredibly true, you know. For me, it took me it didn't, it didn't take me very long to realize that in my industry, you know, visibility is good for some and bad for others, despite the fact that you still identify in the same way, you know. For me, for example, the amount of And I know, I just I needed to have money. But I also wanted to kind of negative hate that I get, yes, it's there, but it is no, in no way on an equal playing field as if a black trans woman or a trans person of color were to be in that situation. And I think that is something that is completely forgotten the intersectionality of transmitters forgotten when when transmitters there, because they think that they're ticking the box, so they don't really, necessarily look at the other boxes that were involved when it comes to race, ability, religion. You know, one of those things, they don't think about the nuances. And yeah, I do agree, what I've learned is with visibility in terms of my, what I say, and what I bow into the world is that I've realized that visibility for me, it's not actually that important. I don't, at the beginning of my career, I was the Yes person. I was like, Yes, I'll do that. Yeah, I'll do that. get into this industry. And now I've realized, I guess quite fortunately, that I don't need to say yes. I need to reserve myself and preserve myself. Because if I don't have anything to say, then I don't need to speak. And I think that's a really important thing to that I've learned is that, just because there's an expectation on you to be in these spaces, and to speak up and to say these kind of quite empowering things. It's like, well, actually, I don't have to do there, there's no real expectation to do that. It's just a perceived expectation that comes from being visible. You know, I'm very much enjoy now being very selective with what I do. Very conscious of what I do, because it's important, so important to do that. We have a question.

Alex Iantaffi:Absolutely. I saw that it was something about can presence and thoughts on our presence simply being enough. Is that the one that you were looking at as well? It was, yeah, yeah. I love that presence being enough. And it reminds me of one of my friends and and here in community, Andrea Jenkins, who talks about was a very openly African American trans woman and city council are now talking about being in the room changes. So right that that point about presence, and yeah, love to hear your thoughts about presence being enough.

Jamie Windust:I think definitely, like I said, just now there's a there's an element to it, where it's like, if you are if you are there, and you make people listen, and people are just able to witness your presence in a space? Absolutely. There's power in that. And I think again, it comes with this idea that I was saying where there's often a lot of expectation. I get a lot of messages from people that are kind of going into work or going to uni or going into new industries, and they're trans and they want to kind of, they want to change the workplace, or they want to change their environment. They want to overhaul it and make it trans inclusive. And I'm like, No, that's obviously not a bad thing. But I think and I'm not saying don't do that, but what I'm saying is, do you want to do this? Or do you think you should do it because of the expectation that you think is upon you to go into change it? That definitely, in my experience, I found that and I think that question is right. If you just go in you yourself and your present, that is not there is that there's such kind of disparity in terms of how powerful we are in society and how much expectation is put on us. And how the less kind of the more marginalized theres more pressure or more expectation on you to be perfect. And, you know, it's like if you see how often in the queer community when queer and trans people ever say the wrong thing or don't speak up on certain things. And it can be very easy for them to be kind of shamed in a way. But then if you were to look at wider society, look at all of the white cis men that are just kind of spouting rubbish. You know, that's maybe a bit of a difficult analogy, I'm not saying that people shouldn't be held accountable. But I just think expectation is something that's really important to acknowledge there.

Alex Iantaffi:Yeah, I agree. It's like, sometimes I think about as the pressure of representation, you know, right, and kind of almost being put on this like pedestal, and it's like, yeah, but rather than being able to simply exist as a human and not alongside other humans, who is very fallible, I've definitely, like, have use language that's outdated now to talk even about my own identity, or transcendentalist. Because I didn't know any better, you know, that I've used words that now Generation Z, would be really outraged about like, female body, the male body, that man, I realized that that actually reinforces the binary. And there are better words, right. But it's, yeah, it's this pressure of representation can feel really heavy at times. And so. Yeah and often comes from the outside, right? Yes. I love that question. Right? Is this what you want to do? Or is this what you feel you should do? Because that's the, the pressure on you to kind of represent community in a certain ways or move community forward? In certain ways, and that's a lot to carry in a lot of ways.

Jamie Windust:Yeah, but it's worth it to the day, where we're only people, you know, but and I think, especially in the literary world, there's almost an immediate, there's a presumption that people think that they know you very well, or that they think that you're incredibly I don't, I don't like this word, but incredibly famous or incredibly, like, successful, or, you know, everything's perfect. And they kind of think of you with this, again, they placed their expectations of what they want from you, or what they think that you should, and are like, and it's like, no, I'm just someone that has, you know, we're just people that have happened to have fallen upon a platform. And, like everyone else, we're learning publicly, and we're learning gradually, you know, we just happen to do it in ways that more people may see.

Alex Iantaffi:Exactly. And hopefully my hope is always that by being vulnerable, and being human as much as I can, whether it's in my writing, or whether it's on social media, that hopefully that encourages other people to be a little bit more open to each other humanities, because it can be dehumanizing, homeless, sometimes, kind of the visibility within the community. And that's, that doesn't serve anyone. And there's a difference between that and being accountable. Right. I always want to be accountable to community. Absolutely. If I mess up, I want to be called on as Sonya Renee Taylor talks about, you know. The let's call on each other, you know, when we're not living up to our responsibility to be respectful, and inclusive, and in every way we absolutely can. And there's a difference between that and the dehumanization that sometimes gonna happen. I was like, yes, expecting immediate access, or somebody who know, will read my books or listen to my podcasts, it's going to know a lot about my life. But I didn't know anything about theirs. So there's a little bit of a weird imbalance there sometimes. And I'm sure you experienced that too. Right. And that can be a little awkward sometimes to manage. Yeah.

Jamie Windust:Yeah,it can be very awkward. And I think, yeah there's a definite expectation that people once they almost see us as resources that they can take from. And I think what I found as the writer is that and this has been a fairly recent revelation, I guess, but in the past kind of year or so. I've realized that although I see quite vulnerable moments online, I decide to do though, you know, no longer I'm kind of falling into the strap of expectation. I make a very conscious decision to share that it's not. It's no longer because I think I need to, it's because I want to, and I have a desire to. And what I think that comes with is people just presume that you're in a complete open book. And that, you know, you share everything and that you're these things. And social media definitely doesn't help that sometimes just people constantly want access. So yeah, boundaries have been really important for me, do you find that in your work? Because obviously, as you said, a recovering alcoholic, I meant academic, somedays? Do you find that people kind of want a lot from you or want a lot of advice from you?

Alex Iantaffi:It can happen and that sometimes people usually it's more, I feel like the most trans and non binary folks and queer folks are actually really respectful and mindful. But sometimes this, you know, especially cis, white folks who have a certain level of entitlement, might ask for resources or something, and then get quite upset if I don't respond right? I had a cis person who wanted me to go and talk to their employee group, for Trans Day of visibility, and I was like, great, this is my tea. And it was a big corporation, like big corporation. And they were like, Oh, we're the employee group, we don't have any money. And I was like, this is really problematic. So you're asking a minoritized person, self employed to do work for free when you're such a large corporation. I mean, community, I will give everything I got as within my boundaries and my capacity. Right? I don't owe that to a problematic corporation. Right? It goes back to that tokenizing. And being seen as a resource, but some sometimes people get quite upset. And like I said, folks, when more dominant identities, I think, is that piece of entitlement can get quite upset when you're not as available. And you're like, well, this is a chance for you to educate us on that. And it goes back to what you were saying, I was like, Well, do I want to educate you like your large corporation? If you want my expertise? Absolutely. I can come and educate you. But I don't owe it to you. This shouldn't be like, consider yourself lucky trans person than giving you a chance to talk to this, you know, a large audience or that give you this exposure? I was like, no.

Jamie Windust:Yeah, it goes back to that. The grateful Yeah. mantra that you should be grateful. And it's like, well, no, like, this analogy has been used many times before. But if we were, like you say about going in and doing talks, I've definitely experienced that. It's like if I had any other form of service, if I was doing like, I was a mechanic. God forbid, but if I was a mechanic, and I went in and you were like, oh, no, we're, we're actually up on it. We actually want you to do this for free, because it will look good on your CV. The mechanic would obviously say No, thanks, bye. And what we arguably what we do is a lot more emotionally intense than what a lot of people are required to do in their jobs. So yeah, definitely financial. That, yeah, it's a massive problem. And it's a struggle, but hopefully with pride this year. I don't know about you, but pride for me, it's kind work is beginning to kind of float in and I'm already kind of like, No, my brain can't take it. I'm already worried that I'll collapse if I take it all on.

Alex Iantaffi:Yeah, like what you said about boundaries. And for me, it's like during those moments, it's like, also, there's like a broad community. And sometimes I'm like, well, actually, whose voice can I uplift? And also, you should you know, is this a paid gig? And is this a paid gig that I can pass on to somebody else in community, you know, especially like, trans folks of color, were often not seen as palatable in certain environments, where by I might be approached, because I'm like that people see me as trans masculine, and I'm light skinned. And so that's appealing to them. And I feel like here, I actually have somebody who will be much better for this, and you should also pay them. And it's also kind of relying on community and creating new norms. I love there's a common of somebody who's in this position with a large corporation, who was tapped to work on an inclusive project, and is being asked to recruit more people from the community. Yeah, I would be absolutely nervous for protesters because it's like, what is this about who who benefits? Who's compensated for their labor? Right? All of those that. Yeah, absolutely.

Jamie Windust:Yeah, I'd say in my experience, last year was the first day that I kind of properly started doing consultancy, on predominantly on Pride working on kind of campaign material. And it involves as like questions as it involves kind of having to go to other people and say hello. You know, I'd love you to do this. And it is scary. But I guess what I'd advice in a way would be to arm yourself with as much information as possible. To arm yourself with like that, you know, like you say, is there compensation? Who else is doing it? What is the framework like? Is there safety provisions like all of these things, just try and go in with like a very open dialogue and make it clear that you're, they're open for questions. And try not to feel disheartened if things don't go to plan. Because often, it's nothing to do with us, it's to do with another person's fears or another person's insecurities and all of those things. But yeah, it's an incredibly difficult thing to do. Because we know as trans people, how vulnerable it can feel to go into spaces. And like the questions as in work and inclusivity, and to feel with your guard up a bit, you know, to kind of be in that fight or flight. And that almost ask other people to try that and be like, I want you to come here. And it's going to be fine, can be stressful. Just as we as we neared the end, I've got a final final question for you. What? And this is a very broad question, I apologize. But for people, for people that are watching, or people that may watch, what advice would you give to someone that wants to get into the literary world? Or the publishing world? What kind of one nugget of advice would you say this and don't ever forget it?

Alex Iantaffi:That's a hard question. Oh might need to think about that for a minute. I know, I realized that I looked at the time. And I was like, oh, Jimmy, and I just really got into it. We didn't read anything from our books. Oh, that's great. That was like, but this is so fun. I'm loving it. I was like, Well, I think in terms of advice. I think for me, the great reminder, in the great anchor is write what you want to write, which, you know, seems really, really simple. But I think there can be so many pressures in the publishing world, like, what are the trends and what does your editor wants, and what does the public wants. And so for me to go back, and of course, being open to feedback, it's very helpful, being aware of the trends can be really helpful. But ultimately, I write because I feel there are some things that I've processed in certain ways that I want to share with the world, and has to be my voice and my message, I'm not going to be somebody else. And so I think if there was one piece of advice is just know what you want to write about and stay true to kind of your own voice and to your own vision, even when it seems difficult or when it gets rejected maybe by some people. The publishing world is really vast, you know, even if some sections that may reject you, there are so many different publishing presses, there are so many different editors, different mentors, different agents, whatever it is, it's okay, if you have a strong vision and a strong voice to stay true to yourself. I don't know, maybe sounds really corny and cheesy, but I think if there's one thing that's mine, what's yours?

Jamie Windust:Yeah, no, I completely agree. Yeah, it I know what you mean, sometimes when I say things like that, it can feel a bit cheesy, but it's true, you know, core, what you've said is completely true. Yeah and I guess to echo from our whole conversation is to make sure that you do something that you love, and to not do something that you think you should do, because what can happen, what what if the biggest mistake that I made was to do that, and then you end up forgetting the things that you actually have a passion for. And also, with writing, you know, with writing a book, you have to have a real hunger for it. You have to have a real like appetite, a real kind of investigative nature, but just just a desire to because it's a long, you know, it takes a long time. It's, it's a really long process in their shoes to kind of from the initial kind of meetings to publication, like nearly three years, so is it a long time, so you need to really, make sure you love what you're writing about. Love what you're doing. And look after yourself. Look after yourself, because it's whatever you write about. It is an incredibly difficult thing to sit down as one person and write a whole book. incredibly difficult. So yeah, this has been lovely. I love you.

Alex Iantaffi:I know, I was like, this is wonderful. And also for people who don't know, like, this is the first time we've met each other. So this is just really beautiful. And I'm loving every moment of it. Looks like there's a request of could we end with a reading? How do you feel about that? Like reading a little bit?

Jamie Windust:Course. Do you want? Do you want to? Have you got it there with you?

Alex Iantaffi:I do have something ready from my book. Do you have something ready from your book?

Jamie Windust:Yeah, you go first love.

Alex Iantaffi:Okay. Yes, I had a few things. But then we got into this beautiful conversation and I was like this is so much fun. But I will read. I'll read from the last chapter of my Gender Trauma book, and it's the section that is called collective dreams, visions and possibilities. And it's a chapter around moving towards healing. What is the decolonial understanding of gender? We cannot be in the same river twice. I don't believe that we can go back to a mythical pre colonial past. We cannot erase history, trauma and just pretend it never happened, or is still happening. As a trauma therapist, I witnessed these desires on an individual basis almost daily. So many of my clients with wish to just forget, pretend whatever happened did not happen, or think that eradicating the perpetrator in some way, might bring peace. However, when there has been a wound, the wound needs to be tended to. It needs to be noticed, cleaned and treated, and it takes time to heal. What would a pre colonial past even look like for many of us, were involuntarily or voluntarily displaced in a number of ways, including due to gender violence. I think that comfort and connection can be found in the past, but I'm not so sure that our future can be found there. I've written elsewhere that to think about the future directions of non binary genders is science fiction, and a number of much better authors than I have engaged I continue to engage in those questions. I do know that healing from gender trauma is a landscape that I do not know if we can even begin to imagine. However, it is a critical feeling of the possibility that has not come to be yet. I sense into it when I'm around other people will actively challenge normative ideas of gender in favor of authenticity, no matter what their own gender identities and experiences might be. I taste it when I'm in communities where consent, healing, and relationships are at the center, the heart of what we're doing. I smell it in the wind of younger generations, who often no longer think like us when it comes to gender, but are still shaped and impacted by our trauma. I believe that healing from gender trauma lives in the spaces between us the spaces across which we tried to reach for one another when we dream of community when we create structures centered around healing, justice and liberation. When we strive for disability, justice and access, when we dare to envision inclusive spaces. There is no definite answer here. No list I can give you our magic formula for how to fix the painful impact of this historical, cultural, intergenerational and social trauma of a rigid gender binary. However, I believe that if we can start to notice the wound, engage with it critically, start to clean it up within and between ourselves, we can start to plant the seed for another world of possibilities. This is a world in which we're connected to the past where we do not deny or erase our history, but do not get stuck in it. Rather we move forward reclaiming what is ours and creating a new what was destroyed. This book is a long open ended invitation to the stream of gender liberation, for our collective healing. How will you respond?

Jamie Windust:I love this sensory language you use, like the smell. I love that very, very, very clever. I'm just gonna turn the light on because I've realized it's got dark.

Alex Iantaffi:It's much later where you are, absolutely go for it.

Jamie Windust:I'll leave this here. So I'm gonna go with the section from the chapter around mental health. This chapter is called the stapler and the jelly. One thing I always think about when it comes to my own mental health is the image of when someone spended a stapler inside amount of jelly. Yes, that's right. A stapler in jelly is what is the one visual depiction of my mental health that I have chosen to put in the writing here for you. If you don't know what I mean, pop the book down and going up, Google. It's a whole entity suspended in a translucent fruity casing that you can see through. To the untrained eye, it may look impenetrable. The stapler is being held by the matter around it. However, one slice through and it will follow and no longer be encased by the fruity support that is found yourself with it. Similarly with my brain and my mental health is something that is a whole living, breathing thing. And instead of being surrounded by jelly, it's being held together by me. In this analogy, the stapler is my mental health, and the jelly is me. My thoughts, my brain, my actions, is being held by something that you can see. You might have to squint to work out what it is, but you can see it is tangible, you know exactly what, but just like a stapler in a manner of jelly, sometimes you can't see mental health for that actually is. You have to spin it around, squint, hold it up to the light and study it to truly realize what you're looking at. Our mental health can often feel like this. When we are living such busy, stressful and nuanced lives can feel like thoughts, feelings that we are having are actually just normal. They're simply part of our existence, a sidecar to our main body in which the negative feelings and coping mechanisms we enact on a daily basis to deal with the way that the world treats our bodies, becomes normalized in our own hurts common play every day. I think many non binary people believe that our lived experience and the impact that has on our mental health is something we can't change due to the fact that the staring the comments, the misgendering, the abusive language on anomalies, that everyday occurrences. So we often stop trying to navigate the after effects in our minds when these instances happen, because we're so used to them, we become numb to our own trauma. But being numb doesn't mean you don't care. It just means that it doesn't surprise you. It doesn't shatter your world or throw you off center. It just sits on top of you. You don't really feel it, you know it's there. Like when a part of your body becomes numb, you can see the pressure being applied, but you can't feed a single second of it. This for me is why it became so hard to realize that my mental health was so bad. Because it had become so commonplace in my day to day life to feel down. They didn't actually realize that my permanent mood was now in fact so well.

Alex Iantaffi:Thank you for that. That is powerful. That is a powerful part of the book. I remember when I read the book. This image is unforgettable. Yeah.

Jamie Windust:Thank you so much. It's been an absolute

Alex Iantaffi:This has been wonderful. I know that was that dream. sometimes Joe said people share what they're reading. I don't know if you if you want to do that. But I know I want to uplift this book by to Lawrence was actually local to me and was also published by Jessica clean slate and its the trends self care workbook, which is honestly a lifesaver right now. I love the joy and the celebration and the exercises and just the beautiful drawings. That just some of the drawings are so joyous and you can color them in anyway. I just wanted to uplift the

Jamie Windust:I love that love that. Yeah, no, I've got some

Alex Iantaffi:Absolutely. Well thank you so much. This has been so just beautiful and nourishing and thank you for people to people for tuning in. I think we're going to try and save this. So maybe some of you are watching this later. And just a reminder that you're interested in Jamie's beautiful book or my amazing books at the moment around autism and gender, book but you can get both of them from Pages of Hackney they ability, disability and gender I think yeah, JKP are brilliant. can be delivered by bike to you if you live locally or they can If you don't know them. They produce kind of academic and be posted or you can go pick it up or browse in the store. Just nonfiction focus books on gender and sexuality. They're wonderful thank you as well Pages of Hackney for this opportunity. and they're also always looking for authors. So go and go and And for us to get to know each other really in front of get involved. everybody.

Jamie Windust:I know. Thank you. Yeah, thank you Pages of Hackney. Thank you to yourself. You've been wonderful. And yeah, I will see you very soon.

Alex Iantaffi:I hope so. Yes. Bye.

Jamie Windust:Bye my love.

Alex Iantaffi:Bye.

Podcasts we love

Check out these other fine podcasts recommended by us, not an algorithm.