Gender Stories

Gender Stories

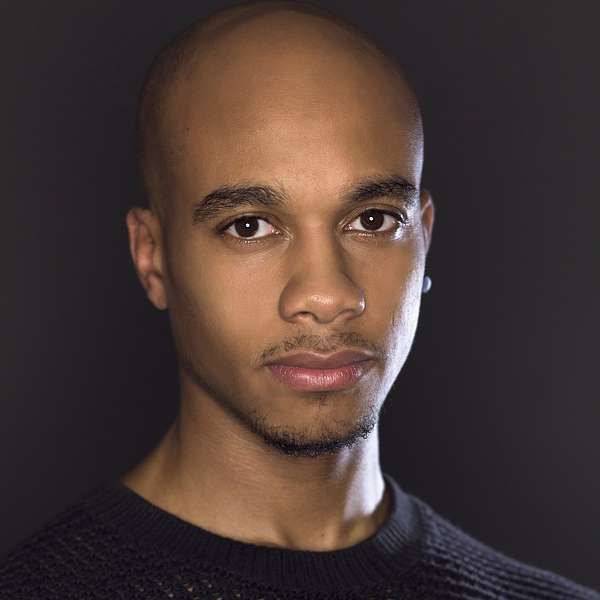

Black Boy Out of Time: a conversation with Hari Ziyad

Alex Iantaffi interviews author, artist, screenwriter and speaker Hari Ziyad about their new book Black Boy Out of Time. They talk about family, mental health, gender, growing up Black and queer, abolition, ancestral grief and wisdom, and healing.

Hari Ziyad is a cultural critic, a screenwriter, and the editor-in-chief of RaceBaitr. They are a 2021 Lambda Literary Fellow, and their writing has been featured in BuzzFeed, Out, the Guardian, Paste magazine, and the academic journal Critical Ethnic Studies, among other publications. Previously they were the managing editor of the Black Youth Project and a script consultant on the television series David Makes Man. Hari spends their all-too-rare free time trying to get their friends to give the latest generation of R & B starlets a chance and attempting to entertain their always very unbothered pit bull mix, Khione. You can find out more about Hari at https://www.hariziyad.com/ and follow them on Twitter.

Instagram: GenderStories

Hosted by Alex Iantaffi

Music by Maxwell von Raven

Gender Stories logo by Lior Effinger-Weintraub

Everyone has a relationship with gender. What's your story? Hello and welcome to Gender stories with your host, Dr. Alex Iantaffi.

Alex Iantaffi:Hello, and welcome to another episode of Gender Stories. I know I will say that I'm excited but I truly am. And I cannot wait to share this interview with you gender stories listeners, and I cannot wait for you to read the book that this amazing person has written. So today I am sitting with Hari Ziyad who is a cultural critic, screenwriter, and the editor in chief of Race Better. They are a 2021 Lambda Literary fellow, and the writing has been featured in Buzzfeed, Out, the Guardian, Paste magazine, and the academic journal Critical Ethnic Studies among other publications. Previously, they were the managing editor of the black youth project and a script consultant on the television series David Makes Man, Harry's spends their ultra rare free time trying to get their friends to give the latest generation of R & B starlets a chance and attempting to entertain. They're always very unbothered people mix here. So welcome. Thank you so much for coming on to gender stories.

Hari Ziyad:Thank you. I'm so excited to be here.

Alex Iantaffi:All right, well. I really appreciate you making the time. And like I was saying in the introduction, I really truly love your book. And so let's start from there. Tell the listeners about this book that's out and why you wrote it at this particular moment in time.

Hari Ziyad:Yes, and thank you, I'm glad you enjoyed it. My book, Black Boy Out Of Time is a memoir that just came out at the beginning of March, it documents my experiences as one of 19 children and a Hari Krishna and Muslim family and my mother was Hindu. And what it meant to navigate the carceral structures that were around us that are influencing that experience and healing from that now as an adult through an abolitionist lens. So the book is about abolition as a healing practice. And it just is just documents how I made it here as a journalist and writer that I am today. From Cleveland, East 128th Street to New York.

Alex Iantaffi:Thank you. And yes, thank you. Sorry, I should have also named the title of your book. So thank you for catching that and actually giving the title of your book to our listeners. And I'll make sure that of course, in the episode description, you're gonna have links to Hari's website and the book. One of the there's so much that I love about the book that I can hardly pick a starting point. But when I was reading it, what was really what I really loved about the book is that, for me, it was was a book about healing. It's a book about faith. It's about abolition, like he's had about family, and the experience of growing up black and queer in this world where anti blackness is so incredibly pervasive and shapes the life of black children, and no, and it's also a book about trauma and grief and healing and ancestral grief and historical trauma and hope. So that's why it's so hard to even pick a starting point. But maybe let's start from where the start the book, in some ways starts with you. Kind of creating the term misafropedia for a specific type of experience. Is okay if we start from there?

Hari Ziyad:Yeah, that's perfect. So you want me just go into like how that came to be?

Alex Iantaffi:Yeah, just how that came to be like, and why did you feel the need to create a specific term, which I think it's really at the intersection of gendered and racialized experience right away. So that seemed like a good place to start given the focus on gender of this podcast.

Hari Ziyad:So my work has always revolved around black childhoods, and that's been around for a long time. And so I've always had this like frustration with a lack of language around the specific experiences that black children have and In the specific ways that childhood and blackness intersect to affect those experiences. But when writing the book, I just it really came to a head, like if this entire book is going to be about that, then there needs to be something that kind of guides and ties it all together. And so I was also inspired by the way that misogyny noir was was created by Moya Bailey, a black feminist scholar to describe how sexism and anti blackness intersect in the lives of black women, which really did a lot of great, great things in pushing conversations forward around black women's experience, and in the last couple of years. So I was hopeful that with a term like misafropedia that we could talk about things like the school to prison pipeline and talk about things like the identification of black children, and talk about all of these things in a way that kind of brings it all together. And ties it also to carceral logics and the carceral system. And so that is what I was hoping to do. And so misafropedia just literally means the oppression that black children experience, specifically. And I found it so necessary when writing this book. Because like I was saying, this book is so much about like black childhood trauma, but in particular, it's about the separation that black people... With separation that I have from like my childhood experiences, which I was able to tie to the carceral state and carceral systems and carceral logics in throughout, and so misafropedia, is used in the book to try to combat that separation between us in our childhood selves as adults, which I think is a really important part of the healing process that we need to as that we all need, but in particular that black people need if we're going to ever live in a world where we're a little bit more free.

Alex Iantaffi:Absolutely. And again, I was like, oh, I want to go in three different directions at once. I want to have a conversation about healing, and this beautiful sentence you have about healing in the book that I want to talk about. But before I do that, actually want to stay a little bit about with the writing of the book, if that's okay. You know, you're a black Carter, right in this book, as I was reading it as like, I'm Italian, I'm an immigrant here, and I'm a light skinned person. And there were things I could connect to. But our experiences are very different in so many different ways. And I was wondering, do you feel like you were really fighting for a black audience? And it's fine if other people get something out of it? Because that's how art and rriting works. Right? But who was the audience in your mind? If that makes?

Hari Ziyad:Yeah, no, I'm always writing for black people. And so it's always really fascinating. And I love having these discussions, because I think we don't, we are so preoccupied with like reaching wider audiences that we sometimes forget that you can still do that. And still be very intentional about your, your core audience. And so my work has always been able to resonate with other people. And I'm not like actively not trying to talk, I'm on this podcast, I think we're gonna have a wonderful day. But I'm always very intentional about writing to black folks. And I do that, in particular, because I think there's so much that's lost when you're constantly responding to other gazes, and particularly like, the white gaze. And I mean, that's the that Toni Morrison quote that is always going around about how white how racism is such a distraction to the work that we need to do. And so when I'm writing with black people in mind, I find I have to do much less of like responding to, you know, people saying you using the race card, or like your race baiting, which is why I chose the name of race beta, to kind of preempt that whole conversation. Because I don't think we always have to constantly respond, there are some things that we know. And it's okay to say that we know and we don't have to constantly explain it. And I also think that other people are much smarter than we give them credit for. And if they want to come along this journey, they'll find a way in. So I'm really grateful that you were able to find your way in and come on this journey with us but definitely writing to black folks, and in particular to black people who are interested in doing this journey themselves as well. This book is about people who might want to heal through that same kind of trauma that I'm healing through. And I hope that it gives them some skills that they can use along that journey. Because it's such a process, and it will look different. And so even that is not as specific as it can be that audience because every, even all of the black people in the world, like there are so many different audiences with even the ones who want to do healing work. So even at a more specific level, I was writing for me and writing for my inner child, and writing for my family. And, yeah, I definitely welcome other people coming along in this journey, but I think it's fine for writers to be that specific with their audience.

Alex Iantaffi:Absolutely. And I, yeah, I didn't know I, I loved it. And there was so much that kind of resonated across the differences. And yeah, no, no, every reader is like, yes, it's a broad population and, not everybody's a white American. And there were so many things about family even just being brought up in like, a Catholic Italian family in Italy, not in the States, which is a very different experiences. But there were moments like when you talk about your grandma, like I could feel, I could feel it in my body, like that connection to my own grandma and that chip and, and just that sense of family, even across the cultural differences. Anyway, I found it beautiful, and I loved it. To our readers, whatever your race or ethnicity or culture, you should read this book, because there is so much good in this book, from so many perspectives, for so many point of views, and, and let's go with the healing the you talked about healing and talk to you in some way this, you wrote this book for yourself. And you have this beautiful line about healing in the book, which is this society has conditioned me to believe that healing is just the muting of one's rage. And as somebody who's a healer, who was the therapist was a lot of criticisms of the therapeutic framework. It got me in the cat in so many ways. You know, but yeah, this society has conditioned me to believe that healing is just the muting of one's rage. I feel like there's like multitudes of essays in one line. I don't know, maybe it's just me, but I really loved it. Do you want to say a little bit about the healing as meaning of your rage?

Hari Ziyad:Yeah. And I'm so glad that that line resonated, because I think that's so critical to so much of what I was struggling with is, and I think that a lot of marginalized people struggle with is that we have very legitimate reasons to be enraged about things. And so when we spend so much of our lives, judging that part of us, how could we ever be hold, and so for a long time, I would like reject it, the whole therapeutic model, because I had so many experiences that were that were like that, and I was like, This just doesn't even make sense to me. But there are other ways to heal, that don't require you to, I mean, the only legitimate ways I would say that don't require you to, to cut off of a very important part of yourself. Anger, rage, sadness, are all just emotions that are part of the human experience. And we deserve to be able to fill them now how they're, how we show them and express them, we could have conversations about what healthier ways of doing that. But I think we have to start at like that. It's okay, especially when we've gone through what we've gone through as black people in this world, it's okay to feel that rage, and then we can have a discussion of what that looks like when it's expressed. And so that was like the starting point for me. That was when I was able to go back to into therapy was when I found that therapist that it didn't feel like that with all the time. And that is when I was able to make the most strides in my own healing journey is by legit is by acknowledging my rage and honoring it as a part of me and an important part of me. And using that as part of my rage is a central part of a lot of the healing work that I do. And that's that's a good thing. Yeah, so I'm really glad that line resonated with you.

Alex Iantaffi:I like highlighted. I was like I have 500 feelings in this moment. Just you know, partially some of what you said about and of how much systems of oppression Thrive right on the silencing of the anger and rage, whoever is oppressed and how that's perpetuated through systems are supposed to be about healing, but they're often about conformity, right? It's therapy or yes, I've have a lot of criticism of those models, and also just how, culturally folks are so dissociated from anger and from themselves and from an have such fragility around anger and rage, which is always seems to be striking to me.

Hari Ziyad:I read a really interesting tweet, I forgot who tweeted it. And it was about how, like, women have been presented as like, the more emotional gender. And I was like, I think that's the tweet was talking about how that's only because we've disconnected anger from the idea of emotion. So like, that we don't have access, like white men are very angry all the time. But it's not even thought about as an emotion, often, which I thought was a really interesting way, especially when it comes to like men. It's not it's, it's just the the way to be a bit in this world, which I thought was really interesting way to put it.

Alex Iantaffi:Exactly. And I think that anger gets completed with behavior, right? It's an emotion that you're feeling and that you can express. It's about like behavior, they're seen as, okay or not, okay. But also, who is that behavior seen as, okay for right? I remember, like moving from Italy, to the UK, all the sudden, I went from being a quiet introvert, to really loud, rude extrovert, because I didn't know the cultural rules. I was happening. And I was really young at the time, you know, and it took me years to really unpack kind of just the xenophobia and the context in which some of the stuff that was happening was happening. And I always say to a couple of folks here who don't understand what's happening on in terms of white privilege. And the uprising, which is literally after happened in May, after the murder of Mr. George Floyd, which is literally in my neighborhood, where I live. And I'm like, I don't even understand how this whole country and has not been burned down already, by both indigenous folks and black folks. And, and when I look, when I see Anglo white folks look at me with a question in their eyes, I'm like, the trauma is so deep, the trauma, dissociation from anger is so deep that they can't even understand like, once they start to understand it, I think it's almost too too big for them to hold, because they'll... Am I making sense?

Hari Ziyad:Yeah I think that makes sense. If they were to acknowledge it like, where would that lead them? Like, if you notice, I think that's part of it is that once you start to, to get to the point where you're at where it's just like, oh, there's so many different legitimate reasons why all of this could be burned out. But what does that mean for if you're white, like you're home, and you're the wealth you inherited in the land that you're on, and like, you, if you're not ready to give that up, then you can just dismiss all of that and say, this is completely invalid. Because we're not ready. We're not having conversations about what that would look like in terms of wealth redistribution, and redistributing the land and like, which is where we need to get eventually. And so yeah, it's really, I see that happening in real time because I don't think they're unable to understand it. I think that it's just to acknowledge it would put them in a very bad position.

Alex Iantaffi:You're right, thank you for that reframe. I think is so terrifying for them to acknowledge it. I mean, we're together. It's not like I mean, literally, I'm blocks from the third precinct to like our, our house. We were scared that our house would burn down. And I also got it I was like, of course, like, this neighborhood. It makes sense. It makes...

Hari Ziyad:Black people are afraid too. That's the why is that they've they've done such a good job of letting us internalize all of that. And so that we start to police it, which is what the book is about, like we start doing that policing of ourselves, so that I mean, there's doing it too. But it works so well, because we're even when they're not even when they're not actual police officers in our neighborhoods in our homes. We've internalized so much of that policing, because we've also internalized that fear, what would the world look like for us with if all of this was redistributed like that? Scary. if we haven't started talking about imagining how how, what a different world could look like, which is why abolition is such an imaginative process, because you have to be able to get to that point where you can start talking about things that would change the entire world. And really think about how that could be good for us. And you have to give yourself space to imagine that first. And we've been living our life so long with everything that is erected just to limit our imagination. So it takes a while to get to that place. But I hope the book helps people to start imagining bigger.

Alex Iantaffi:Absolutely. And I love that imagination piece, which I think it's and that, yes, that's where my brain was going on to us, like that policing piece, right? How many? How that policing is internalized, and it's impossible to escape even within family, which is something that you talked a lot about in the book, too. And I know that when even I remember a training I did a couple of years ago, and for therapists and this black therapist was also appearing came up to me and talked about really starting to realize how much police gendered gender, and the intersection of gender and race because it's so the fact,. Why understandably, of any black boy deviating from masculinity, and now that can be punished, culturally and socially and by the police. And in every way, it's terrifying. Try it. And so that piece about how the policing is internal, but it's also intergenerational, and it's within the family, and especially when there is that intersection of gender and race and queerness used as a bigger umbrella to encompass gender as well as sexuality. And, and that's a lot of what's in the book, too. Right. Yeah, and, and other any, it's a tender, you talk about a very tenderly, in a lot of ways, and in this like, very direct, but very just full of healing intention that you're writing. Does that make sense?

Hari Ziyad:Yeah, I love that phrase full of healing intention. That's, yeah, that's exactly what I was aiming for, is like, there are a lot of conflicts that are documented in the book. And there are a lot of conflicts that I experience, and a lot of them are with people I love and like my mother. And I think the difference between a punitive culture and the world we could have if abolition were to be successful, is that we could approach conflict with full of healing intention. And I think you still address it, like you're saying you're still very direct about it. But it feels a lot different. And it's going to have different results. And so, yeah, my, my hope is that everything that I write, and everything that I do, has that same healing intention. But it's a journey, especially when you've lived in a world where it's so easy to just punish people and punish things. And also back to our earlier point about like with anger, we've been convinced in a lot of cases that healing can't involve rage, and what do we do with that? When it can and so we have to unlearn that. And then, then we can get the full scope of what a healing intent could look like. Because I don't think that I don't think I'm there yet. I still I think I'm still figuring out, like, what healing could look like when I'm angry, like, if I, if I was to see Donald Trump tomorrow, like in front of me, like, what could I approach that situation with healing into it? Like, I'm still figuring that out. And so, but I think the intent is the part right is like, and that's something that you have to cultivate and bring into your life and practice. And that's what I was trying to do in the book.

Alex Iantaffi:I think it comes across beautifully. And I'm glad that we're back to anger in some ways because anger is very mobilizing, but who gets to be angry? It's not a given right in a lot of ways. And so there are a lot of, there are lots of moments of conflict. Like I said, there are lots of moments in which there could be anger in lots of different directions, right? Coming up black and queer. And I know you use they/them pronouns, but I don't know would you identify as non binary?

Hari Ziyad:Yes. Simplification. Yes. I mean, I, we're talking about gender in blackness and the intersection there, I'd still feel like non binary is as comprehensive as it could can be for me, but I think, just for ease of compensation.

Alex Iantaffi:Like, yeah, no, I do want to go back to that, and especially chapter 11, when you that's called, like, my gender is black. And I definitely want to go there next. But now, of course, so that's both right, but so good. I was thinking, yes, there was a lot to be angry about, in some ways coming up in a world where there's a lot of anti blackness coming up in a world where there's a lot of rigidity around gender, let's say and be more gender expansive, that those rigid gender category would, would allow for coming up. And the the anger could go in a lot of different directions, right? Because there's conflict with family, there's conflict with systems. What moved you from anger, to abolition? Because that's not where everybody goes, right. You know, anger could go towards carceral logic and punishment, and push back and conflict. Not generative conflict, but really like, yeah, you know, what I'm talking about? Am I making sense? How did you make that leap?

Hari Ziyad:I think I mean, I think the short answer is, I'm still figuring that out. I think there's a lot of times where I do go to that punitive, carceral place.

Alex Iantaffi:Punitive. That's a word that I was looking for.

Hari Ziyad:And it's so ingrained that it's something I'll probably be wrestling with for a long time. But I think how abolition became like a part of my intentions, is through watching my grandmother and seeing how that... So my grandmother for the book, for the listeners, my grandmother, she struggled with bipolar disorder, for most of our lives was untreated. And that resulted in a lot of like, terrible mental health crises where police were called, and just seeing how detrimental that was to her overall healing, even though like, so many times. That was like, the only thing that we, my mother thought there was, she could do, and watching my mother try out have an understanding of this as not being like, sustainable or not ultimately, being healthy. Try so many different things. And seeing how like that was such a expression of her care and her love, and seeing how, in the moments where she was able to find an alternative, like the difference and how my grandmother's life was affected, but in turn, are all of our lives that kind of like set the seed of like, oh, like, there has to be something different. And like if my mother's tried this hard, and like, yes, maybe she didn't always succeed in finding a solution. But she was trying for a reason. And I can continue doing that work. And so that was like the seed of it. I didn't, I wasn't really thinking of it in terms of abolition back then. But especially as I got older and developed a different relationship with my grandmother, when she was in a little healthier place. And seeing that, like I had so much of the anger, that it was legitimate, because there were a lot of horrible things that I experienced as a child that I shouldn't have experienced. But I directed so much of it at her and without, like ever, without ever acknowledging like her own mental health struggles without acknowledging everything else that was going on. And that, to me, illuminated that there could be another way because the anger was still there. So even while I was developing this new relationship with her there was still the anger there. But it could be used in a different way. And so, so much of my journey toward abolition has been informed by that and about trying to reestablish a relationship with my grandmother, specifically, specifically after she passed away doing altar work and being able to have that kind of relationship with her now that like me, she's not I can engage with her without even the struggles that she was living through. Even when she was healthier, like towards the end of her life. And being able to imagine what that engagement would look like, through altar work allows me to imagine how I can engage with other people who might still be here differently, and allows me to engage with my mother. Like, oh, what if she wasn't dealing with all of these things that she was dealing with when she and I had this tension around my queerness and sexuality, which doesn't mean that it doesn't exist, and doesn't mean I'm not angry about it. But I can engage her knowing that there is a possible world where that is not the case, because there's a possible world where she wasn't taught all of these things, too. And so my anger gets directed to the world, in the system that shaped her. Although, I mean, some of it is still directed to her. And I think that's fine. But I think ultimately, it recognizes what's at the root of it. And in order to do that, you have to, like we were talking about earlier, you have to be able to acknowledge first that the anger is legitimate, before you can direct it to a place that's legitimate. And so I got it took a lot of me understanding and being able to finding my new therapists who was able to legitimize that anger that I was feeling, in order to me to come to where I am now, but I think I'm still on that journey.

Alex Iantaffi:And it's such a long journey. I know, for myself, and for a lot of my clients to that journey of reconciling kind of understanding the broader context in which things are we're not okay at them sometimes, way too many of us with family members, and understanding our you know, in your specific context, how much of that is born out of anti blackness and settler colonialism and racism, right. That all of this bigger misogyny, and then we suffer pedia and all of those big contexts, and yeah, it's also in the relationship, right in the personal relationship, and I love what you said about how much healing that can be in engaging with ancestors. Grandma, what I would call an ancestor, and you can engage for that altar work. Yeah, in my experience, that's different to doing pastoral work, rather than like leaving family members where there can be a different kind of tension, at least in my experience.

Hari Ziyad:Yeah, it opens up so much. Like, I think that was what made it easier for me to do inner child work to is, so it was I started doing altar work. And I mean, growing up Hindu, like, I was kind of familiar with the concept of it already. But the idea that you can have a different relationship, or you can continue a relationship, even though you're told that, that you don't have a connection to that person anymore. And I think for like, it's very useful to be told that as for the society to continue, like they're intentionally trying to strip us from as black people from our histories. And so getting a lot of that power back through ancestor work is kind of parallels the healing that you do with inner child work and the child that you're told that you don't necessarily have a connection with anymore, or you feel that you don't have connection with anymore. And once that's possible, you're like, oh, maybe it's possible to create a whole entire new world?

Alex Iantaffi:Absolutely. I mean, I think so. But you know, I'm very much of like a optimistic, Pisces, it's unlike any world is possible. It's just gonna take a lot of work. And it's not all like, it doesn't look harmonious. I think that the path, you know, towards kind of a abolitionist kind of vision does include really acknowledging that anger and the hurt and we can't bypass it. I think sometimes even white folks who want to engage with abolition kind of want to bypass the rage. I was like, you can't bypass the rage. Because there needs to be repair. Because if the, you know, abolition is, yeah, and abolition is vision still includes harm happening and repair being possible. And in my understanding, and my....

Hari Ziyad:No Alex I completely agree. I was at a abolitionist conference and one of the white panelists and I were getting into a debate because they said that the concept of enemies is not abolitionist, and I was like, wow. To offer you as a white person, but that's not the case. And we've like done, we've been doing abolition, indigenous communities have been doing abolition, knowing that they've had enemies that they've also had to fight against. And so it's really interesting, but I think, like we were saying earlier comes from a place of self preservation, like if you're going to engage in this abolitionist work, it would mean giving up so much as a white person. And if the rage isn't there, then maybe you don't have to face that rage because some of it might be legitimately trained on you. And we have to learn how to and that's what's so beautiful about this healing work is it also teaches us how to receive rage and how to receive hurt that in the accountable for a harms in different ways, because we're not just expected to push it away. Or say that it's just harmful, evil or bad. We have to really do the work to just to sit with something and someone who we might have harmed and repair that, which is the only way that I've ever experienced harm being repaired in my families with myself and my communities. And I think if we're going to ever have a world that ever moves past this white supremacist framework, that's what's going to have to happen with white folks as well.

Alex Iantaffi:Oh, absolutely and anger is such a gift. Because it's like if somebody is angry with me, and there's enough relationship that they can tell me what a gift whereas you know, what a younger white folks doing is like, trying to bypass anger or pretend there is no anger reminds me of like a conflict with a friend. Who was like, I feel like when you're angry, you direct your anger me, I was like, well, if I'm mad at you, would you want me to be mad at like, I'm mad at you with you with your behavior. And I'm telling you because I want to repair. And I was also like, it's not like you're not mad. It's just that your angers cold and dissociative. And you just cut me off. And don't talk to me. That doesn't feel great. That's still anger. And you could see the light bulb going on. Like I was like, it's not the white people don't do anger. I think my experience Anglo white folks do anger in this like really dissociative, cold way where they're like, oh you don't even know what happens sometimes. And you're like, what happened? Last time to say, I was like, I don't even I didn't even know we were in conflict, let alone were angry with me. And how can there be relationship and repair? Like if, if we're not capable of giving and receiving anger with one another? Right? Cuz that's a human emotion that's gonna happen. And it's part yeah, all of that, that you said, I'm just kind of connecting, because that's how my brain works. I hope that's okay. I feel like I want to talk more about anger and about abolition. But I also know that my podcast is about gender. And you have this beautiful chapter. And that was titled as my gender is black. And I want you to talk about that. So I feel like I'm like, pulling myself back from the abolitionist track that would want to talk more, and maybe we'll get back to it more this.

Hari Ziyad:Yeah, I think it's connected for sure. Because I think the ways that we construct gender is rooted in these very putative ideas that are binary, and that don't give room for people to to be their whole selves in the same way that we could talk about anger, I think they are very much connected. And in particular, the experience of black people who then they're trying to make sense of gender in this country in particular, which is a country where we were brought

Alex Iantaffi:We're a figment of people's imagination. here most of us as a ungendered subjects. Like people who were, we were slaves, and like we are gender only meant as much as it could create more slaves. And so that chapter is about like, what it means to try and find gender in a society where gender was not designed for you. And what does it mean to? What does it mean to reject that concept entirely? And not, because I don't think that we can be gendered. And I just think that the ways that we think about gender under this society has never given room for black people. And so in that regard, I would say like all black people are a gender in that sense. And but I think that there's other ways to find gender, other ways that we've done gender, that might be more useful in figuring out our place in whatever world comes after this one. But yeah, I think it's totally tied to the concept of what you're allowed to be and what is acceptable to perform. I think the ways that even rage and like we were talking about earlier that rage and anger are even conceived and tied to gender, it shows up differently. Like when a woman is enraged, she's hysterical. And when a non binary person is raised, they don't exist, because they're...

Hari Ziyad:If men are enraged, that's just the way that like, it's the behavior like you're talking about. And so I think all of that is going to feel restrictive to black people in particular, because it doesn't give I think it's gonna feel restrictive to anyone, because it's doesn't give anyone room to be their whole selves. But I think even more so for people who those concepts have only ever contributed to us being commodities, and us being sold and exploited. It's going to take a new idea, or it's not even new, I think it's a lot of this is these are ideas that have been around for a long time, but it'll take a different idea of gender than the ones that we're taught here in this society.

Alex Iantaffi:You make so many, yes, so many good points is like, you know, because in exactly that, it's like this kind of settler colonial rigid idea of the gender binary, is sold, I think and package in kind of Western dominant culture as if this is the natural way of things and the way things are, and the way it's always been. And it's actually not it's a product of settler colonialism and white supremacy and the transatlantic slave trade and all of those kinds of things together and in one, yeah. How did you find your way to your own current gender? And I say current because I also believe that our gender landscape evolves as gender No, I just turned 50. And the way I relate to my gender now 50, it's really different than when I was 30, or 20. And, yeah, it's different now. That's the best way I'm still processing and in some way, but so how did you find your way to your current gender through all of that, all of that historical trauma and wisdom and connection and lack of connection and all of that?

Hari Ziyad:Yeah, I think where I am, and my gender journey is always related to like, my journey towards my healing with my inner child also. Because for me, I think where I started having a shift is like, there was a time at least, and maybe I've made this all up in my head. And that's also possible, but there was a time where I wasn't thinking about gender in that way. And or at least, it wasn't conscious to me in that way. And like gender wasn't the thing that limited me from like, who I could express love to how I could dress and just be in the world. And so what were the things that I was, what did I gravitate toward during that time? It's finding, rediscovering that through the inner child work is always going to be what's scaring me on my gender journey. And that's just like rediscovering different things. I love rediscovering how I like to wear my clothes. It's like, and I don't think it's always like a conscious thing. But I'm much more aware of when something does come up, like Oh, I like that because like, that's reminds me of this experience when I was a child and like that, just that was what felt good that and so I think I'm always just on this journey of trying to get back to a time that and maybe like I said that time didn't really fully exist in this lifetime. But maybe it I think I'll go wherever it takes me maybe it'll take me before this lifetime, maybe it will take me to my grandmother and it's already has done that with the alter work and maybe it'll take me beyond that with whatever other research I do in my family tree, but it's always about like trying to rediscover who I was before I learned to hate my gendered body. So yeah, that's where I am now.

Alex Iantaffi:I got tearful when you said that because as you were describing that I had this feeling of your gender journey, and correct me if I'm wrong by felt like your gender journey is so guided by expansiveness and expansion, how can you expand into possibility for that inner child that maybe never had that space to really fully expand into whatever gender identity and expression was joyful and pleasant, pleasurable and pleasant. And when I think of how much our ideas of gender lead us to constriction, you know, describing, I've got a book on the gender and trauma and I talk about, it feels like we're collectively all holding our breath around gender, because of all this intersection of like, settler colonialism, and all those other things that we've already named, that there's so much policing around gender, that we're all kind of holding our breath and having this constriction and part of the work is to expand and during work has to be intersectional. Because we cannot talk about gender and not talk about race and not talk about settler colonialism and all those things. And it was, I don't know, it was just so moving to hear talk about the work. I know, it felt really guided by that feeling of freedom and expansion. I don't know if that's how it feels.

Hari Ziyad:No, I think, I think that feels, that rings true. And at the very least, that's what I want it to always I wanted my gender to not be something that restricts me in a world that I've already been so restricted. I want with every new discovery about my gender to feel a little more free. And so that's where I head whatever it takes me towards that feeling is where we're my next step is on the gender journey.

Alex Iantaffi:Beautiful. What I love also is in in your book, you don't shy away from naming that, regardless of your own experience of oppression around gender or policing or limitation, how you've also participated in harm sometimes, because how could we not live in a system that is so rigid when it comes to gender and so policing that we haven't participated in that harm and some way of perpetuating it? Right. And and again, I think it comes back to this idea of abolition is also being really accountable for our participation in systems. About the in the book even in your family relationships that yes, and yes, anything about that.

Hari Ziyad:will always bring up like, what do we do when rapists and murderers and but it always goes to, there's a reason they bring up rapists and murderers because they don't want to talk about the harms that they participated in. But when you see abolitionists in action, you'll find further the most part, that we're engaging in accountability practices with all of these harms already. And so we're showing what you do, we're trying to demonstrate I mean, a lot of times we fail and we make mistakes. But part of the process of being an abolitionist is to show what you do when harm is part and you have to be willing to show when you do when you're the person who's who has harmed other people, because we all do that. Hopefully, we don't do it to extent where they're like they've been oppressed by us. But we've all harmed other people. And so, I mean, it's really important to situate that in our own lives, and in our own communities. And I don't think it's worth just talking about it to pat yourself on the back and like, Oh, I'm accountable, but but I think it is important to show what the working through that process looks like. What are the challenges? What you still might be struggling with? Because I still do struggle with that. And so that's what I wanted to show in the book.

Alex Iantaffi:And I think you did, I think you did it so beautifully. You know, I'm kind of looking at my notes and going oh, there are so many, so many quotes that I could pull up. But I also want to be respectful of your time, although I will pull up one quote. Which kind of I think to me that connect you talk about this quote talks says the most depressing thing about being queer in this world, is the fact that isn't just the possibility of your sexuality that you're taught to be afraid of a world where you can hold the person you love without guilt terrifies you, too. I've never held another boy in my arms. I've never been held that way with my consent either. And I've been taught that was never supposed to feel that much joy. So I could only beat myself up when I did, which is, for me, what I love about that quote is that is that complexity, right? Again, of like, it's not just being accountable for the harm we can do to others, but somehow that even join us to stay a little bit in this constricted place. This expansion is scary and terrifying.

Hari Ziyad:Yeah, most a lot of the harm that we do is to ourselves, as in that this book is about is about how so oh yes, I've harmed other people. And a lot of that just for the their own privacy, like, I wouldn't want to necessarily bring that up. But so much more of that. I mean, so much more consistently like those same ideas like we don't avoid pointing them into ourselves, like we use the same tools that we've used to move throughout the world against ourselves. And what does it look like to be accountable for it to yourself to like, that's just as central to this whole process of abolition is here is working through your own inner conflicts, and figuring out when you've harmed yourself and how to be accountable to yourself and redress for the harms that you've committed against yourself, also. And that's the hard part. And that's why having a good therapist is really great, because they can help you with that, hopefully. But yeah, that's the hard part. And it's also like, I think too often it's removed from the other work that we have to do as abolitionist, but it's so central to all of it. Because if we can't model that with ourselves, how are we going to model that with anyone else?

Alex Iantaffi:Exactly. Yes, I could keep talking about this for hours. But like I said, I want to be respectful of your time. And dear listeners, if the idea of abolition is new to you, there are also two other episodes of Gender Stories where I talked with Deanna Ayers. And actually one is just me and Deanna, and the other one is me, and Mike, John Barker. And Deanna, and we talk about abolition. So if this is the first time you've heard about abolition, you might want to check this out. And of course, that leads you to other resources. But just to kind of bookmark it for folks if they want to delve deeper into this. And also read Harri's book because it's, it's so good. It's so good. I just can't even find a better words that is so good, and everybody should read it. But like I said, I want to be respectful of your time. All right. And so is there anything that I haven't asked you about? Or haven't brought up that you were hoping to talk about? Or that you would really like to share with the listeners?

Hari Ziyad:Oh, no, I think that was pretty. I mean, I could also talk with you because those were great questions. I could talk for longer, but I think that that felt comprehensive to me also felt like a great conversation. So thank you for that.

Alex Iantaffi:Well thank you so much for being here today. I really appreciate you sharing your thoughts by your process and also just your very personal journey with our listeners and your listeners as ever. Thank you for being here with us. I'll see you next time.

Podcasts we love

Check out these other fine podcasts recommended by us, not an algorithm.